JERRY SCHURR

EVOLUTION

OF THE IMAGE

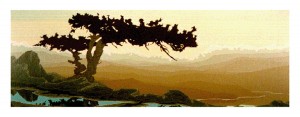

My drawings, paintings, serigraphs and recent digital images reflect a forty-seven year process which began at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in 1967 with my hard-edge non-objective work. The clean flat color and systemic approach of painters Frank Stella, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Victor Vasarely and the color fields of Barnet Newman and Adolph Gotlieb fascinated me.

Thematically, though, I was more emotionally tuned to the Surrealists: Yves Tanguey, Max Ernst and the German erotic artist, Hans Bellmer. My early works were blatantly sexual with color penetration and reception occupying the whole canvas, Nuance was totally absent and each piece had a banner-like quality. The canvases were monumental but generally unsatisfying.

In 1970, my wife, Sandy, and I travelled to Europe; gradually as we wandered the landscape of Switzerland’s lake district-Como, Lucerne and Lugano, a more succinct way of expressing the erotic themes I was feeling began to take place. The deep mountain passes of the Alps spoke to me on a grand scale, and as we drove from Switzerland down through Italy and across the Adriatic to Greece, I began to see the landscape as an endless panorama of exciting, erotic encounters.

But the technical problems seemed the most formidable when I first began to tackle the process of transferring my visual impressions to a more permanent form. How was the structure of this wondrous landscape best expressed – especially on a two dimensional surface?

My solution came from a printing technique. I had begun silkscreen printing as an experiment in 1971. I liked the uniform inked surface laid down by the screen; the hard edge, which was a result of stencil technique, fit my format perfectly. Multiple screen registration – getting one color to meet another flawlessly – seemed, after many attempts, to be both uneconomical and over-complicated as a way to get the results I wanted. I began to use one screen to do all my colors. I achieved this by overprinting each color on top of the other and changing my stencils on the one screen while it was still locked into the printing bed.

One day it occurred to me that the technique I was using was identical to the landscape as I was conceiving it, both in my drawings and in my mind. I began to understand the organization of the landscape in very simple and linear terms. I had developed, inadvertently, an analog of the landscape through reduction stencil technique.

I now saw a way to apply the same system to my emerging landscape paintings. The canvas would serve as both the support for the stencils’ contour and the surface to transfer/cut the image. In place of silkscreen stencil, I would apply masking tape as my stencil material, transfer the image to it and cut it on the canvas to define the plane color I was painting. In other words, I would paint the entire open image area a particular color, then I would mask/stencil only the portion of that color that was to remain in the final painting. Once that was completed, I would go on to the next plane, color, etc., etc. until the painting was finished. I would then strip off the tape and …voila! I’d completed the painting. Off-times I would then paint the results with more intimate details, such as flowers, and other surface features.

The only problem was that the image was hidden from view as the painting process went on; due to this I had to develop an analog color system so as not to lose touch with the images’ color progress. I discovered that I could base/mix each color using the color before it; therefore, every color in a particular painting is derived from all the colors preceding it in that painting. Each canvas is absolutely unique and organically unified because of these interdependent systems.

I work spatially from back to front, i.e., the most distant plane from the viewer is painted first and each plane as it approaches the foreground is painted in the order of its ascent toward the observer. My use of the reflection has both a technical and philosophical basis.

First, technically, the reflection balances and strengthens the horizontal thrust of the ascending planes. The line of the horizon defines the observer’s position in relation to the elements of colors, planes and lines occurring in the picture; the reflection makes the horizons position immutable.

Philosophically, the reflection sets up an ultimatum to the viewer. We start out seeing a picture as the artist’s set-up to have us see both the way he sees and what he wants us to see. The reflection demands the viewer accept the content of the picture as real. Not only is there a view, but it is repeated either in its entirety or in part as a left-handed version of itself. To disbelieve this, becomes a very difficult if not impossible decision for the viewer. The viewer can dispense with the fear that he is being seduced or in some way taken advantage of by the artist. He can feel free to accept the literal content of the picture and can be emotionally impacted upon freely just as the artist was when he first experience the particular landscape he’s expressed in his painting.

At this stage, my work has taken on a life of its own; what was once an expression of a one to one relationships has now grown into an intimate many leveled involvement, where the earth, air and waters dance of a simple step to a basic melody, has grown and a symphonic reality has emerged. The singular dance is now choreography. I feel more like an orchestral composer, getting my visual inspiration from the earth in all its infinite forms.

Jerry Schurr

August 10, 2014